Plan to mine the ocean’s floor draws critics and concern

A Vancouver company is at the centre of controversy over deep-sea mining

By Marco Shum and Joyce Liew

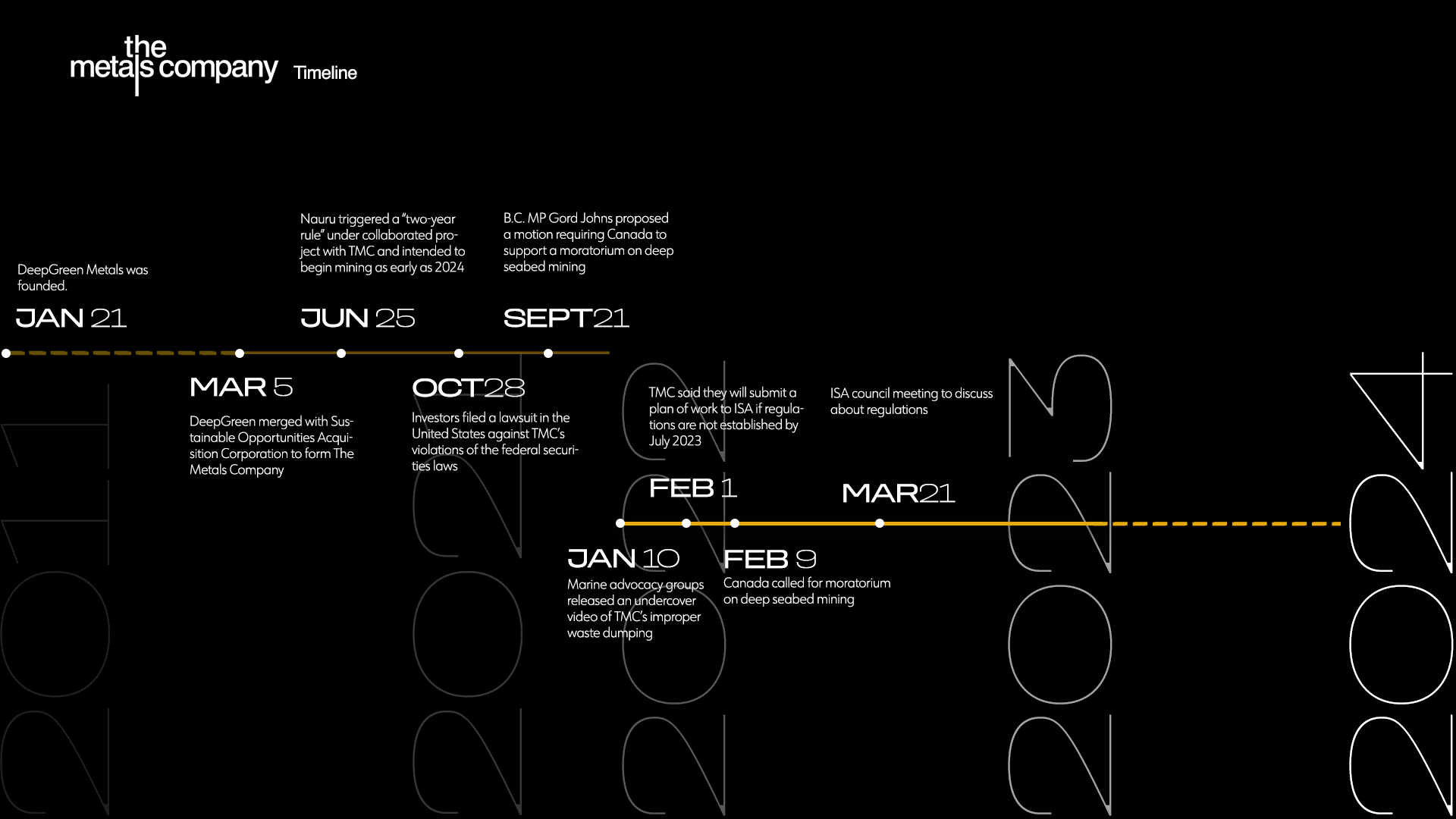

A controversial Vancouver mining company is diving into the darkest area of the ocean floor for metallic rocks rich in minerals they say will bring a greener future.

However, scientists and the Indigenous communities say this will cause irreversible destruction.

Hinano Teavai-Murphy, an Indigenous person who participated in a recent Vancouver protest against deep-sea mining, said she was taught to be humble and respectful to every living species. The practice established a deep relationship between herself, her people and the ocean.

“The ocean is the water when the mother gives birth. So, the ocean heals us, the ocean feeds us, it gives us some joy and pleasure, it gives us life. And that’s why for us, we owe that respect to the ocean,” Teavai-Murphy, who grew up in the South Pacific, told the Voice.

Canada issued a moratorium in February against mining in domestic waters, but that will not stop the Vancouver company at the centre of a deep-sea mining controversy from exploiting the seabed internationally.

Rory Usher, the public relations manager of The Metals Company, said the company is going to pursue a commercial licence for international waters anyway.

“The only thing that the Canadian [government] actually committed to was not to permit mining in their own waters,” Usher said in an interview with the Voice. “International waters is where all the interest is at the moment.”

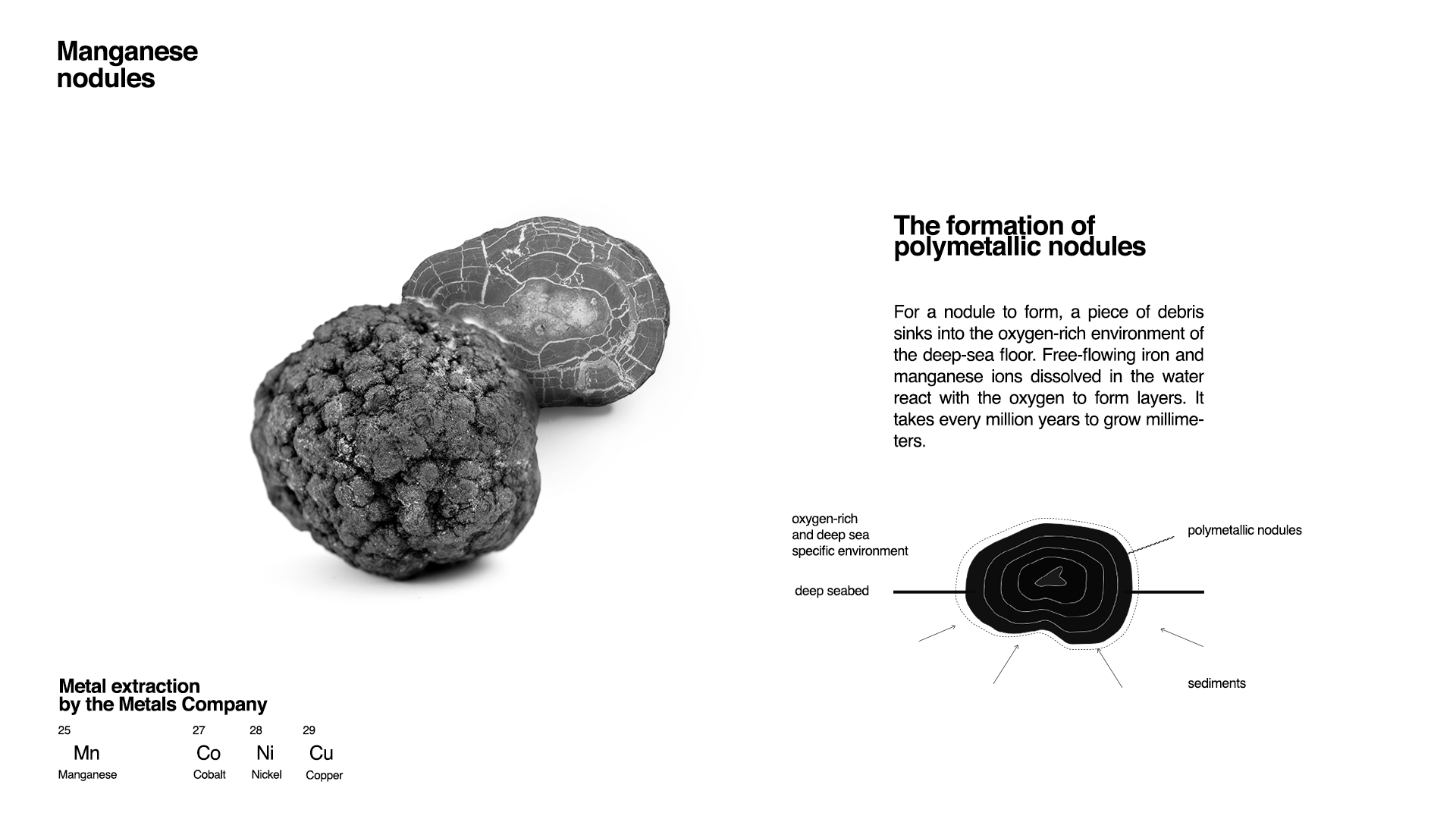

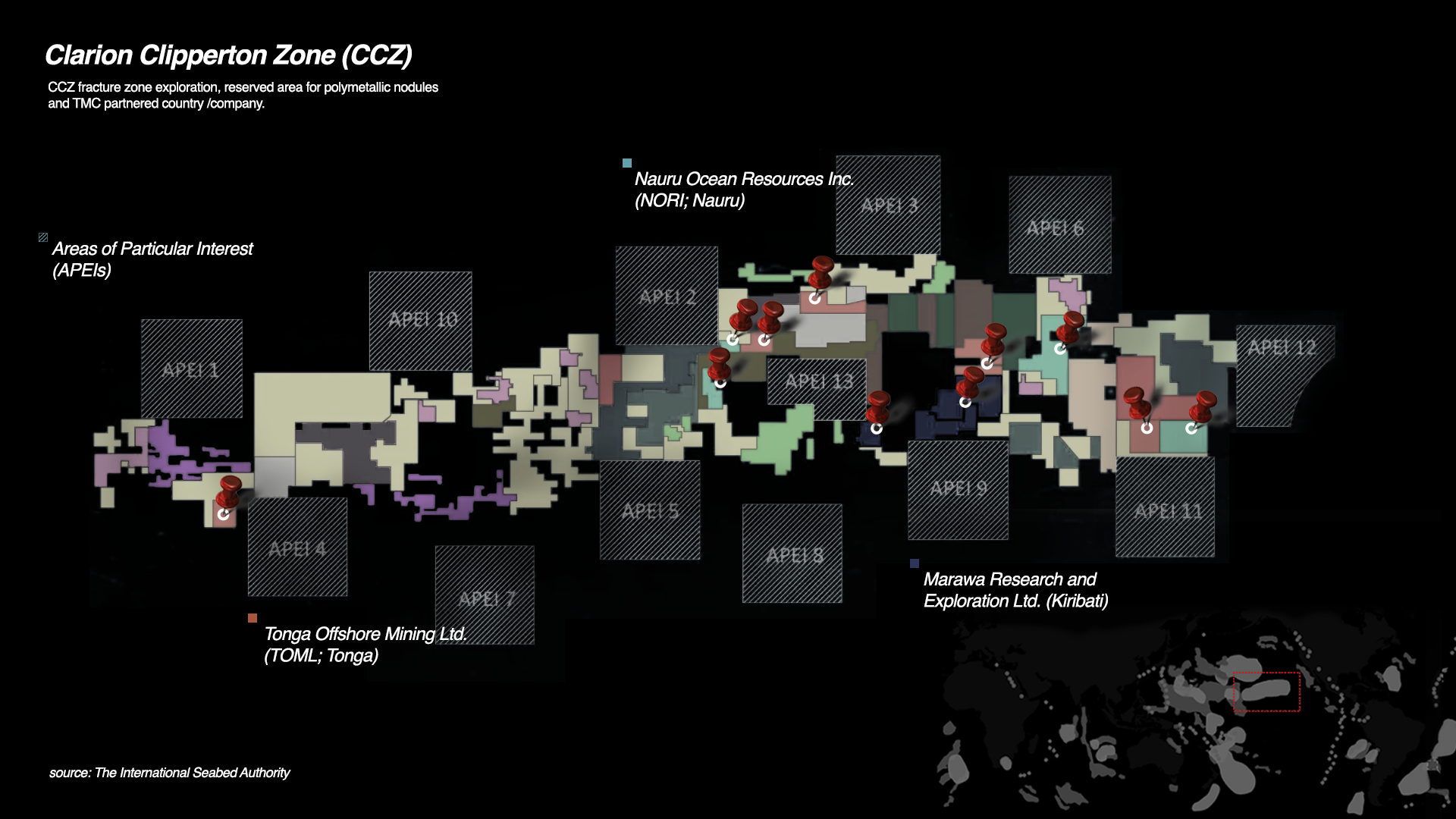

The Metals Company, known as TMC, is a leading player in deep-seabed mining. It is expected to begin mining commercially in the Clarion-Clipperton Zone in 2024. The zone is a vast area of the Pacific Ocean that spans from Hawaii to Mexico containing an excessive amount of polymetallic nodules, known to be rich in minerals used in electric car batteries.

In October 2021, TMC’s investors filed a lawsuit against the company in the United States for allegedly making misleading statements by downplaying the environmental risks of mining the sea floor.

The plaintiffs said that TMC CEO Gerard Barron made a public statement saying the activity generates “zero tailing, zero waste.”

The International Seabed Authority, the regulator of deep-seabed mining in international waters, said in an emailed statement that it is seeing extremely low to no environmental impact in current exploration activities.

But a collaborative research report by the British Geological Survey, the National Oceanography Centre and Heriot-Watt University shows that mining the ocean could drastically disrupt the aquatic ecosystem.

B.C. MP Gord Johns put forth a motion calling for the Canadian government to ban mining in international waters a year ago.

“There have not been sufficient environmental studies on the impacts of deep bed mining,” Johns said in an interview with the Voice. “We need to take responsibility that we’re allowing Canadian companies to go out and prey upon the deep-sea.”

Catherine Coumans, the research coordinator of MiningWatch Canada, said TMC scientists working aboard the mining ship were concerned about practices aboard the company’s mining vessel that they leaked a video of TMC improperly dumping waste into the ocean from the ship.

“They’ve leaked notes that they wrote about how the monitoring was not happening in a way that was credible,” she said. “But they’re afraid to speak to the media.”

But TMC’s Usher downplayed the incident – “that was a brief overspill,” he said.

As TMC is pushing forward from the exploration to exploitation phase, it is required to provide baseline research which presents a thorough description of the environmental and deep-sea habitat impacts caused by the activities. However, British Geological Survey research says insufficient baseline research is leading to the uncertainty to predict the impact of commercial scale exploitation of the nodules.

The survey showed that there was a lack of transparency within the ISA due to limited research findings being released, as well as closed-session meetings. The credibility and maturity of research methodologies are implausible given the collector data “was for three or four months,” the survey stated.

Marine advocates said they are also worried about the ecosystem and biodiversity impact with the commercial operations as the mining activities are poorly assessed.

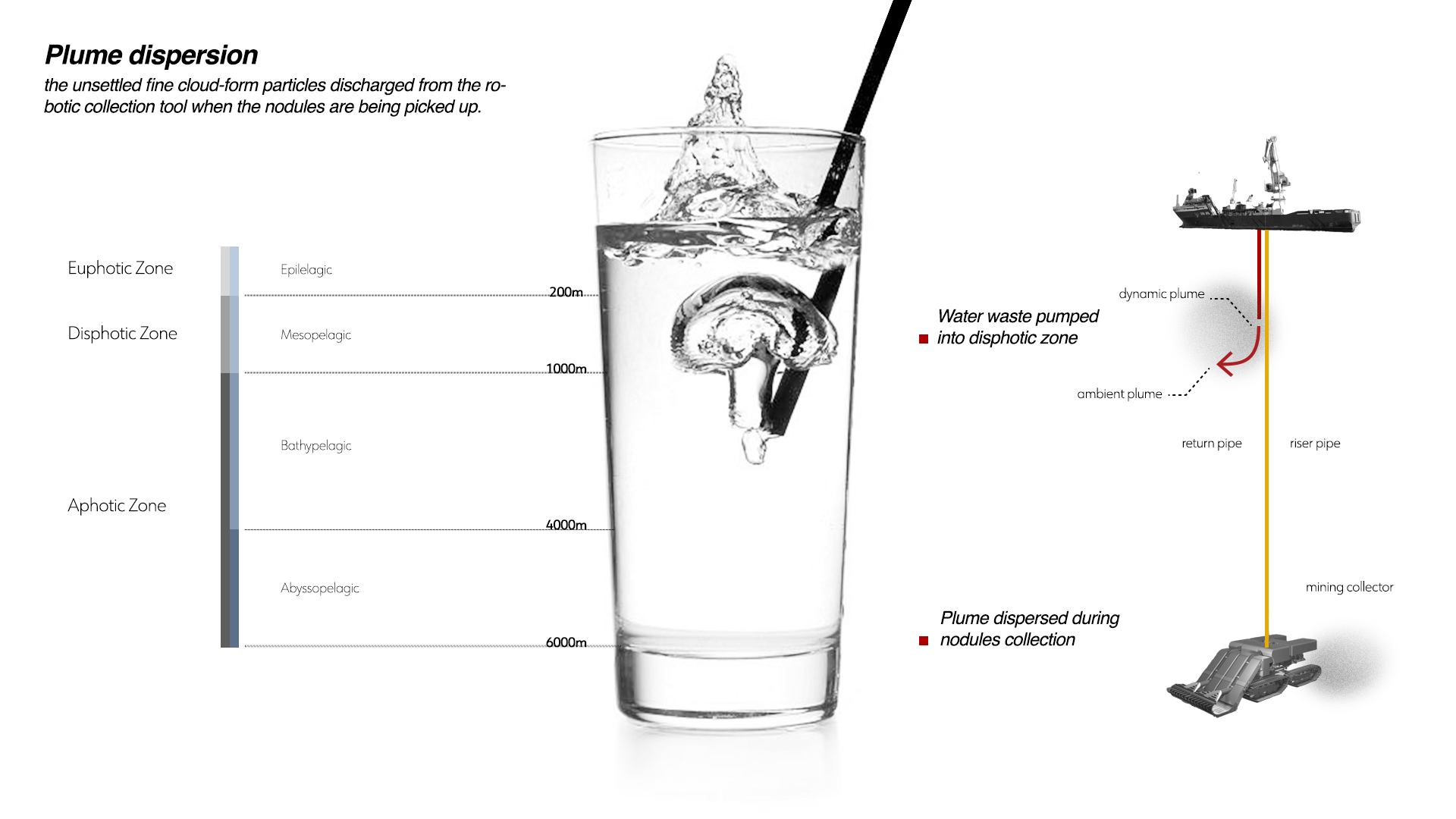

John Luick, coastal oceanographer of Austides Consulting, said the most critical concern is the dispersion of sediment plumes beyond the specific mining area and current mining technologies are not capable of resolving the issue.

Sediment plume is the unsettled fine cloud-form particles discharged from the robotic collection tools when the nodules are being picked up on the seafloor which could be released in the deep-water or mid-water zone.

“If they [exploiters] go down and mine an area of one acre, the area which could be ecologically destroyed essentially could be 10,000 acres from that one acre,” said Luick, who has 20 years of experience in ocean research.

Luick said deep-sea mining should not be allowed until better technology is introduced, as living organisms in the area are not likely to adapt to the sediments.

Added Coumans: “There are even whales … that dive as deep as where these nodules are, which is between four to six kilometers depth.”

A February article in the academic journal Frontiers in Marine Science stated that deep-sea mining operations are negatively interfering with the habitat and migration of marine creatures, such as whales and dolphins. It shows that the cetaceans will potentially be disturbed by the noise of the vehicles.

Member states from the ISA council and scientists said more research needs to be conducted to address the uncertainties of the mining impact, but TMC said they are going to submit a plan of work in this year, even if regulations are not completed by then.

Usher said there is a need for strong and stringent regulations but until now there is no specifics on environmental thresholds to monitor the activities, which is a mandatory submission to the ISA in July to obtain the exploitation licence.

Johns, who represents the riding of Courtenay-Alberni, said he is concerned about the ISA’s lack of transparency and that the regulatory process has been fast tracked. “The metals company notified the sea authority of its intention to start deep-sea mining which triggered a rush to finalize,” he said.

Coumans said the ISA is a completely experimental form of governance over mining like a “black box” and has conflicting mandates.

“Its mandate is to protect this ecosystem for humankind,” Coumans said. “But it also has the mandate to allow mining in the area.”

Comments are closed.